Diyarbakir – What to see and do

Over the centuries Diyarbakir, in south east Turkey, has seen dozens of civilizations and empires come and go. The Greeks, Romans, Sassanids, Arabs, Byzantines and the Ottomans all ruled here at one time or another.

The Mervani, a Kurdish Sunni Muslim dynasty of Upper Mesopotamia and Armenia ruled Diyarbakir between 978 and 1085 AD, and the province was home to fierce Kurdish tribesmen later on. It was also the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch and had a large Armenian population, numbering around 150,000 by the late 19th century, with a total of around 1.5 million Armenians in the province.

However after 1915, the Armenian population counted at less than 100,000. Today the Armenian community is tiny, as is the Mesopotamian one, but there’s still a large Kurdish population. In this now Muslim majority area, Diyarbakir ‘s multicultural heritage is visible everywhere, in the architecture, language and food. There are churches, schools, monasteries, cemeteries and other monuments, many of them abandoned, throughout the city and surrounds.

A few of the Armenian churches and those of other Christian denominations are still in operation alongside the majestic Ulu Camii, and if you know where to look, you can see a minaret and two church spires sharing the same patch of skyline.

On this trip to Diyarbakir I travelled with my husband Kim as usual, but with the addition of newish friends Safi, Stephen and their adult son Cyrus. I met them all by chance on a press trip to Bursa. They were great companions as you’ll see. Here’s what we did.

What to see in Diyarbakir

NORTH OF GAZI CADDESI (main street in town centre)

Diyarbakir Surlar (Diyarbakir City Walls)

We started at Surlar, the massive 5.8 km-long black basalt defensive walls known as Dişkale or Outer Castle, in the historic heart of Diyarbakir. Originally built by the Hurris in the 3rd millennium BCE, the present walls are from the Byzantine era (CE 330-500), and include towers, 82 bastions, 63 inscriptions left by Yezidi, Romans and others, plus massive gates. There were originally four main gates, Harput Kapısı to the north, Mardin Gate to the south, Yenikapı or New Gate to the east and Urfa Kapısı leading to the west.

At the top of this imposing UNESCO World Heritage site, said to be second in extent only to the Great Wall of China, the views of the Hevsel Gardens (more on this further down the page), believed to date back 8,000 years, are incredible. Fields of impossibly velvety green and feathery poplars fed by the water from the Tigris River, stretch as far as the eye can see. You’ll kick yourself if you don’t climb up and take a look.

Diyarbakir Arkeoloji Müzesi (Diyarbakir Archaeological Museum)

Throughout history, İçkale, the inner castle, served as an administrative centre and was a local neighbourhood until the early 21st century. Now it contains the Diyarbakir Archaeological Museum complex. The museum consists of 14 former military buildings, the walls themselves, a Byzantine church and a tumulus. They’re all set amongst pretty grounds made up of rose bushes and mature leafy trees. The café operates out of a former command centre commissionedby Diyarbakir Governor Mehmet Faik Pasha in 1902 for the 7th Army Corps. It has uninterrupted views over the Hevsel Gardens and makes for a shady retreat from the heat.

First I’ll go through what you can see in the main buildings, then talk more about the tumulus.

The Gendarmerie Building inside on the left, just after you enter the complex, functions as the Archaeology 2 thematic exhibition space. As well as finds dating from the Neolithic Period to the present, there are beautiful examples of copper, textile and mother-of-pearl handiworks as well as presentations of mechanical inventions gifted to the Ottomans during their rule. The building was constructed between 1887-1891 on the instruction of Diyarbakir Governor Hacı Hasan Paşa.

The majority of Turks head straight for the Atatürk Museum. It’s housed in the former Military Headquarters Building constructed in 1902 as the Inspectorate Office. The building served as Atatürk’s headquarters when he was stationed in Diyarbakir as the commander of the 2nd army corps in 1917. It was repaired and converted into an Atatürk Museum by the 7th Army Corps in 1973. Even if you’re not an Ataturk Museum buff like me, do check it out.

The building next door to Ataturk’s Museum was originally constructed as the Ziraat Bank Office in 1906. It was later used as an arsenal and has since been repurposed as a Children’s Education Centre.

The building labelled Archaeology 1, located between Ataturk’s Museum and the café, contains archaeological findings from the Diyarbakir region. Finds from Körtik Tepe, Çayönü, Hakemi Use, Kenan Tepe and Karavelyan are displayed on the ground floor. More discoveries from Salat Tepe, Müslüman Tepe, Hırbemerdon Tepe, Kavuşan Tumulus, Ziyaret Tepe, Üç Tepe, Hilar and the Inner Castle take up the second floor. This is one for serious fans of archaeology. The building was constructed in 1889 as a government house by Ottoman Governor Sırrı Pasha and was later known as Courthouse A.

Courthouse B, diagonally opposite the gateway into the complex, was built between 1891-1893 as a grand courthouse during the reign of Sultan Abdulhamid II. According to the museum plan this building houses a reception hall and city museum but it was closed to the public when we were there.

The same went for the St George Church, tucked behind Courthouse B. However that’s because it was undergoing extensive renovations so we could only see it from the outside. It dates to the 3rd century CE.

There’s also a caravanserai dating to theArtuqid Era (early 11th to early 15th centuries). The Ottomans converted it into a prison and it’s now the Diyarbakir Restoration and Conservation Regional Laboratory and Artifacts Warehouse for the Museum Directorate. You can only see this austere structure from the outside but look out for the pointed Artuqid Arch featuring a relief of a lion and bull in combat, dating to 1206-07. You walk through it to enter the Inner Castle.

Last but not least is the Amida Mound orTumulus. This site marks the first settlement in Diyarbakir and dates back to the 6th millennium BCE. The mound is currently being excavated and so is closed to the public however we were lucky enough to get a private tour. A worker on his way back from lunch saw us reading the information boards and led us up to the top, then showed us the underground heating system and reception area.

Fiskaya Şelalesi (Fiskaya Waterfall)

North of the Diyarbakir Archaeology Museum complex, over on the edge of town, there’s a small waterfall that cascades down towards the plains. It’s called the Fiskaya waterfall but unfortunately when we went to see it the glass viewing platform was closed. We didn’t mind too much because it gave us another chance to admire the solid ancient walls on our way there and back.

CENTRAL DIYARBAKIR

Ulu Camii (Diyarbakir Grand Mosque)

Diyarbakir’s Ulu Cami or Grand Mosque is one of the oldest mosques in Anatolia. It was originally the Mar Toma Church constructed at an unknown date and converted into a mosque in 639 CE. It’s believed by many to be the fifth Haram Sharif, that is the fifth Holy Temple in the Islamic world after the Kaaba, Masjid an-Nabawi, Masjid al-Aqsa and the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus.

What you see today are four different sections built around a large rectangular courtyard. The main entrance to the courtyard is on the eastern side, on Gazi Caddesi, the main street that runs through Diyarbakir. An open space where people meet for tea in the evenings leads to an arched entryway, flanked by a symmetrically carved relief figure showing a fight between a lion and a bull, symbolising the struggle between good and evil, said to reference the site’s Zoroastrian past.

The mosque is located in the Hanifi section of the complex. According to some sources, this section was used jointly by Arab Muslims and Christians. This makes Ulu Camii similar in use to the Damascus Umayyad Mosque and architecturally, it’s easy to see the resemblance. At first glance, the design and interior seem fairly basic, but that’s not the case.

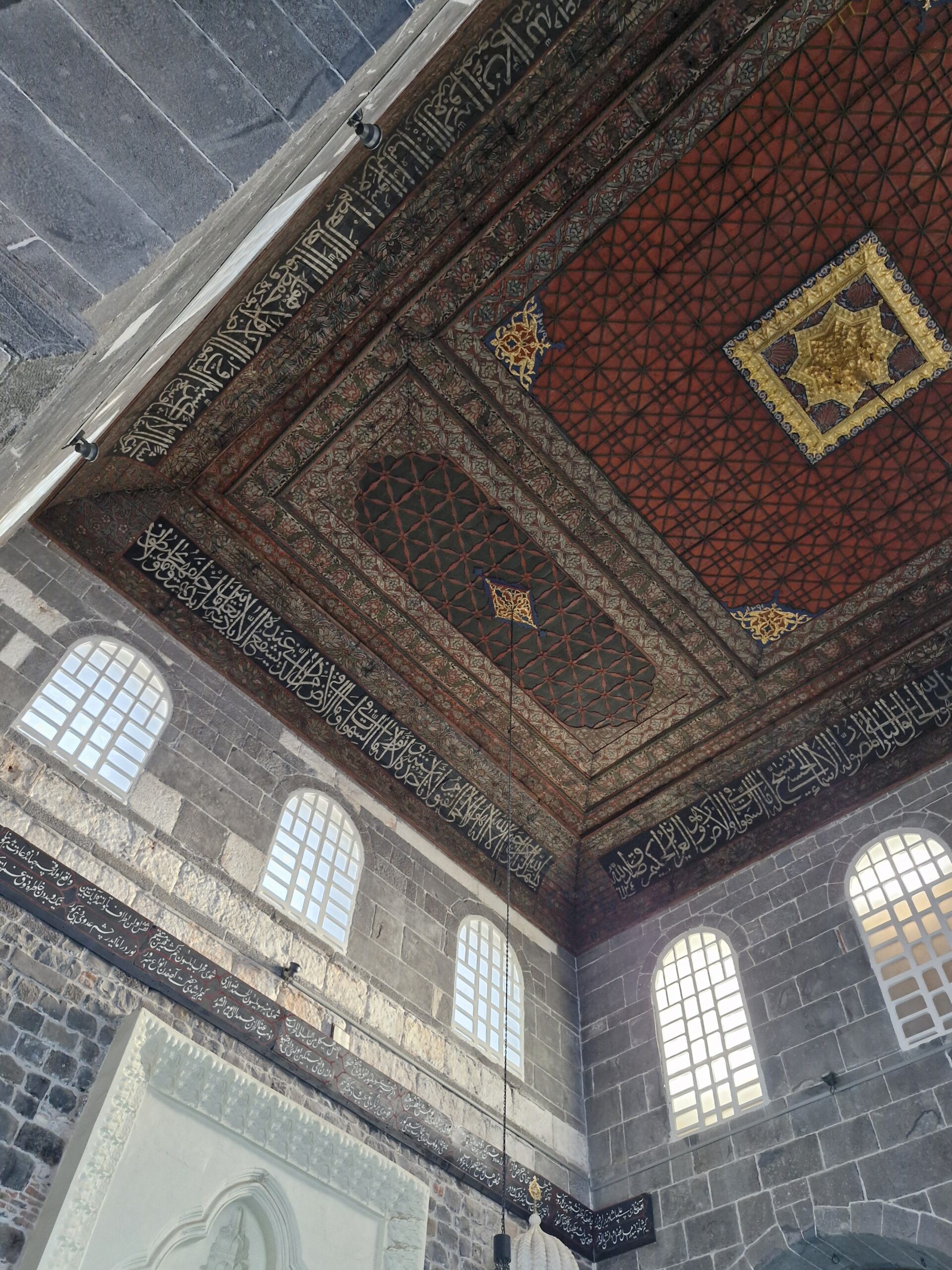

Just inside the door, on the left, is a raised platform on Doric columns. Climb the steep narrow staircase for a closer view of the floral decorations around the wooden girders holding up the richly ornamented ceiling, constructed in traditional Diyarbakir style. There are also strips of hand-drawn writing interspersed with Ottoman period decorations.

The minaret sits on a square column built in 1839 which to my eye looks very similar to a bell tower. The large fountain with pointed dome and octagonal marble columns in the courtyard was built ten years later, while the small sundial over to one side is around 900 years old.

To the north, separated from the main courtyard there’s a small mosque belonging to the Shafi’is, a sect of Sunni Islam and the Mesudiye Medresi. The arcaded enclosed sections, the maksure, are closed off sections used by ağa, bey or sultans, the leaders of the various empires and ethnic groups that ruled Diyarbakir. The Corinthian columns are clearly spolia from other sites, believed to date to the Roman and Byzantine periods.

Elsewhere in the complex there are inscriptions and decrees by Seljuk ruler Melikşah, Anatolian Seljuk ruler Gıyaseddin Keyhüsrev, Akkoyunlu ruler Uzun Hasan and many Ottoman sultans as well as İnaloğulları, Nisanoğulları and the Artuqids.

Other sections of the mosque complex have been converted to administrative offices, including the tourist police. You can read more about each of the sections in this website.

WEST OF GAZI CADDESI

Cemil Pasa Konağı (now Dikarbakir City Museum)

The Diyarbakir City Museum is free to enter and is a great way to learn a lot about the social and cultural history of the city when the population was a mix of Turks, Armenians, Syriacs, Yazidis, Rum (Greeks born in Turkey) and Jews. The rooms of this former private home are filled with displays of their regional clothing along with dozens of photographs of schools, sports days and portraits of women and babies. The newspaper samples are interesting too, such as on June 1, 1976, when an increase in cooking oil and cheese prices made headlines.

I liked the Dengbeji Room best with musical instruments like arbane, tambourines, on display, and recordings to listen to. Dengbeji is a Kurdish music genre sung by Dengbêjs, singing storytellers and the museum contains historical recordings. I listened to someone playing the ney and different people singing including a woman by the name of Gede Lo, which is also the name of a famous song.

Meryem Ana Kilesisi (Syriac Orthodox Church of the Virgin Mary)

In the Syriac language of indigenous Christians, Diyarbakir was known as amid, meaning salvation. Christianity came to Diyarbakir via Antakya and Şanliurfa in the 1st century CE. This Syriac Orthodox church, which served as the Patriarchate of Antiocheia as well as the Episcopate of Diyarbakir over the course of its history, was built in the 3rd century. It suffered severe damage in several fires and was last restored in the early 2000s.

Inside the stone and brick walls with hand-carved walnut tree doors you’ll find a Byzantine-era altar, kandiller, silver lanterns, tombs of some of the saints, relics such as the bones of Thomas the Apostle and Saint Jacob of Sarug. Do stop and admire the astonishing brickwork dome. Although this church is slightly off the beaten track it’s well worth the 50tl entry fee (as of May 2025) and the effort to find it.

EAST OF GAZI CADDESI

Fatih Paşa (Kurşunlu) Camii (Fatih Paşa or Kurşunlu Mosque)

Fatih Paşa Camii, also called the Kurşunlu Mosque as both the dome and roof are completely covered with lead, is located in the Sur neighbourhood. The original building was the St Theodoros or Toros Armenian Catholic Church, converted to a mosque by Bıyıklı Mehmed Paşa (Fatih Paşa) the first Ottoman Governor of Diyarbakir, between 1516 and 1520.

Sur saw some of the worst clashes between Turkish armed forces and Kurdish militants in 2015-2016 in part of the armed conflict that started in 1978 in Turkey. The warring parties entered into a peace agreement in 2025, however Diyarbakir has been safe for tourists to visit for some years now. We felt very welcome and secure during our visit but everyone needs to decide for themselves. Here are my suggestions on what you should consider if you’re concerned about safety in Turkey.

In December 2016, the Kurşunlu Mosque was severely damaged in the conflict, suffering structural damage. Thankfully the mosque was very much intact when I saw it in May 2025, but I can’t swear to the authenticity of what you now see.

The main dome sits in the centre of the structure supported by four square pillars. It appears larger than it is due to the addition of four semi-domes, with half-domes connected to the walls and arches by a large and smaller exedra, a portico where people can sit and talk. Outside there’s a seven domed narthex now used as a porch. When the mosque was a church the narthex was the closest sinners and those not baptised could get to the church, as they would not have been allowed to enter the church itself.

Today the interior is fairly plain but used to be elaborately decorated with column capitals decorated with geometric and floral motifs. The mihrab is made of smooth cut limestone and the qibla is quite ornate, with gold highlights.

After we left Kurşunlu Camii for our next destination, we got lost in a maze of small streets, largely screened by corrugated iron walls. What we could see beyond them was mainly battle scarred ruins and buildings that had been almost completely demolished. Google maps didn’t work here so I kept leading us up dead alleys or back to our starting point. There were few people around and when we did manage to stop an older woman, she didn’t speak Turkish, only Kurdish.

To my surprise, Safi was able to follow what she was saying. Although born in Ankara, Safi is Iranian and as she explained later, Farsi and Kurdish are sister languages. Luckily for us the Kurdish woman knew enough Farsi so that when Safi couldn’t understand a Kurdish word here or there she’d say its Farsi name and Safi would get it.

It turned out a huge section of Sur was basically off limits so we had to backtrack part of the way before we came out on a new, wide road, with an open grassy area opposite recently constructed buildings made from basalt. In the place of vernacular architecture, residences, bakeries, markets and so on, there are now quite luxurious shops selling Calvin Klein, Armani and other labels, alongside upmarket Western style cafes and restaurants.

On the way to Surp Giragos Kilisesi we passed the Ermeni Protestan Kilisesi, an Armenian Protestant church which still has a small congregation of about 70 to 80 people, all of them Muslim converts. Surp Giragos Kilisesi orSaint Cyricus Church as it translates in English, was the largest Armenian Apostolic church in the Middle East from the 16th century onwards.

After the Ottomans conquered Diyarbakır and Saint Toros Church was converted into the Fatih Paşa Mosque, Surp Giragos church was built next to the diocese. In its original form this churchhad an onion-domed bell tower with ten clocks in it, which must have been a sight to behold. Sadly the tower was destroyed by cannon fire in 1914 because its height outshadowed that of the minaret belonging to the neighbouring Sheik Muhtar Mosque.

After the majority of Armenians were expelled from Turkey in 1915 the church lost most of its congregation. German troops took control of it during World War 1 and later on Surp Giragos was briefly used as a cotton granary. It was returned to the tiny Armenian community still living in Diyarbakir in 1960, but was basically derelict until 2011. It underwent extensive restoration and reopened with an official church service after nearly a century of disuse. Once again you can her the church bells ring everyday at 8am and 5pm.

The small Mar Petyun Keldani Kilesi, the Mar Patyun Chalcean Church also known as the Amid Chaldean Church by Syriacs in Diyarbakir, abuts Surp Giragos. There’s been a church on this site since the 4th century, and what you see today, built from black basalt stone, dates to the 17th century.

The final religious structure we saw in this area was the Sheikh Matar Camii or Dört Ayaklı Minare Cami. This mosque is also known as the Sheikh Mutahhar Mosque but it’s most famous for its unique freestanding minaret that stands on four columns. So much so it’s usually referred to as the Dört Ayaklı Minare Camii, the Four-Legged Minaret Mosque. The space between the ‘legs’ is large enough for several people to stand in, which makes for fun photos.

SOUTH OF GAZI CADDESI

Deliller Hani (Husrev Paşa Inn)

Deliller Hani, officially named Husrev Paşa Inn afterDeli Husrev Paşa, the second Ottoman governor of Diyarbakir, is at the bottom end of Gazi Caddesi, near the Mardin Gate. It was built in 1527-28 to provide accommodation for deliller, men who guided pilgrims. The han is laid out like a typical Ottoman caravanserai with two floors built around a square courtyard. The stonework is made up of striking rows of black and white stones, and each room on the upper floor has a window opening onto the street.

It now functions as a hotel but they’re happy for you to come inside and have a drink in the courtyard. Before we went I read a lot of reviews about people being overcharged for soft drinks and so on, but we were served by a very nice man and had no problems. However we did check the price of everything, before we confirmed our order.

We had the time to take a tour of some of the rooms in the hotel. Although they’re quite picturesque, they are small and fairly tired in terms of paintwork and décor. I think with a little love they could be quite spectacular.

AROUND MARDIN GATE AND BEYOND

Keçi Burcu – Goat Tower

Keçi Burcu, a tower built atop a massive rock on the city walls east of the Mardin was undergoing restoration when we visited, but was really worth walking along the path, in the heat, to see. The date of its construction is unknown but Mervani, a leader of the KurdishSunni Muslim dynasty carried out repairs in 1223 and the tower was used as temple during the Byzantine period.

As we couldn’t get inside we didn’t see the 11 arches and column capitals thought to either be spolia from the Roman period or forms dating to the pre-Islamic period. The same goes for the thuluth, an Arabic script variety of Islamic calligraphy and the bird figures reported to decorate the stone here and there.

Due to the narrowness of the path it was impossible to get any shots of the tower, so we made do with taking photos of the Hevsel Gardens. Swoony, aren’t they?

On Gözlu Koprusu and the Hevsel gardens

Next we walked down to On Gözlu Kopru, the 10 Arch Bridge outside Mardin Gate, 3km from the city. It was stinking hot but it meant we could take in the full extent of the Hevsel Gardens, They cover an area of around 700 hectares, run from Diyarbakir Fortress all the way down to the Tigris River and were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2015. The gardens provide an important habitat for more than 180 bird species, otters, foxes, martens, squirrels and hedgehogs.

The bridge has been restored numerous times but some of what you see today was built in 1065 during the Mervani Seljuk period by an architect named Yusuf, son of Ubeyd. The arches are made of cut basalt stone and there are various tea houses built into the terraced banks.

It was lovely sitting in the shade next to the rapidly running river, listening to the breeze shake the poplars. Less enjoyable was trying to get something to drink. They don’t sell tea by the glass, only by the pot, and after our experience in Hasan Paşa Hani (see What to Eat section) we didn’t want to split 600tl for a five person pot and then end up being charged more than we expected, so ordered cool drinks instead.

Other sites to visit in Diyarbakir

Whenever I’m planning a trip I decide what I absolutely have to see, and what I’ll visit if I can. The following are sites I didn’t see, for different reasons.

I skipped visiting this museum dedicated to Turkish poet Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı for two reasons. Firstly, I’ve travelled a lot in south east Turkey and have seen a many small museums set in former homes displaying personal effects and belongings and secondly, because I don’t know anything about his poetry or life and know all the information about him will probably be in Turkish, which makes it harder for me and impossible for most non-Turkish visitors to get much out of it. However the museum’s free to enter and this two-storey black basalt house built in 1820 gives you a good idea of the layout and design of local Diyarbakir architecture.

Dengbej Evi

According to the information I’ve read, the House of Dengbêj showcases the Kurdish tradition of Dengbêj, storytelling by song. Kurdish elders gather here and take turns to sing and chant in a style described as mesmerising. They sing as the mood takes them so there’s no official schedule. While it sounds wonderful we had a packed schedule plus I don’t understand Kurdish so wasn’t sure how much I’d get out of it.

Behrem Pasha Camii

I was really looking forward to seeing this mosque built in 1572 by my favourite Ottoman architect, the great Mimar Sinan. It’s considered one of his most important works outside Istanbul, so I lead our party along run down streets, past cheeky little boys playing football, more corrugated iron walls, smiling women and suspicious men, with great excitement. When I did finally locate the mosque it was closed for renovations. Hopefully I’ll get to see the single dome and minaret, with elaborate muqarnas on exterior doors, sometime in the future.

What to eat in Diyarbakir

When it comes to food it’s a little bit of chaos and a whole lot of liver in Diyarbakir. They cook, serve and eat it 24/7. Unfortunately I hate liver (çiger) but it was never a problem because there are so many other food options. I’d already done some research and when I ran it past the taxi driver on the drive from the airport he was impressed by my choices and told me some of his own.

I added them to my list and we set out to eat our way through as much as we could. One of the best things about the experience was that every time I said “I know a restaurant/café/lokanta where we should try X …”, Safi, Stephen and Cyrus put their trust in me and walked however far it was without complaint.

Like when we went to eat kaburga dolması, beef ribs with spiced rice at Selim Amca. I knew it’d be filling but didn’t factor in their generous ikram, free food offerings, which included bulgur mixed soaked in thin yoghurt, tomato rocket salad, and tomato cucumber salad with nar ekşisi, sour pomegranate sauce.

Wherever we ate in Diyarbakir the ikram was extremely generous. Sometimes we had more complimentary dishes on the table than those we ordered. Not that I’m complaining. Beros Restoran in the new, upmarket part of town I mentioned, served up some of the best, perfect with their succulent steaks.

The wraps at Welat Döner opposite Mardin Gate were particularly tasty. We initially stopped because the man at the helm is a dead ringer for Safi and Stephen’s butcher in Fethiye. The decision to eat there came about when we learned the hard way that the dolmuş back up the hill from the Ten Arch Bridge didn’t go any further. We didn’t mind though because the Welat Döner guy is very friendly, and our delicious lunch, taken from the huge round of döner studded with slices of capsicum, a local speciality.

We ate something new every day, usually healthy, but we couldn’t pass on a slice (each) of Lübnan Künefe at Hacibaba Pastaneleri, only available at their Dağ Kapısı branch. Thinner than Turkish kunefe and made with a different type of cheese, Lübnan Künefe is heavenly with a scoop of Maraş ice cream. This dessert was all the rage so we were lucky to get a table.

Our Diyarbakir hotel came with breakfast included so we only stopped at Hasan Paşa Hani, famous for its Turkish breakfasts that double as lunch, in order to have a look around.Hasan Paşa is the largest extant Ottoman han in the city, packed with breakfast cafes and dozens of Turkish tourist groups on the weekends.

After we’d all looked around we decided to have a break so took a table at Kahvaltı Saray Ömer’i Yeri and ordered a samovar for five. After a while Safi went off with Stephen and came back with a beautiful bracelet so I had her take me to the antique jewellery shop where she bought it (see What to Bring Back section further down for details).

We were having a lovely time in the shop then both received messages from our partners saying there was a problem at the tea house. We went back downstairs and learned the owner had yelled at Kim and Stephen, telling them they had to leave because they were hogging the table, even though the other tables were empty.

When we got the bill it was higher than we’d calculated according to the price list displayed next to the cashier but when we queried it, the woman was incredibly rude to us. We were so incensed we went back to Ulu Camii and spoke to the tourist police there. They wrote down her details and told us we weren’t the first to complain about that particular woman or the problem of price gauging. I must stress though that other than this one experience, we found Diyarbakir shop keepers and restaurant staff to be honest, polite and very helpful.

Sülüklü Han, Leech Han, is a 17th-century-built caravanserai built by Hanilioglu Mahmut Celebi and his sister Atike Hatun in 1683. It was restored and opened to the public in 2010. There’s an old well inside the courtyard where leeches were kept for use in medical treatments, hence the name.

As well as a great range of traditional Turkish and Kurdish specialties, Diyarbakir is open to food innovation, best seen at Ameditan . It’s the brainchild of chef Serdil Demir, a world traveller who came home and fused international cuisine with the Diyarbakir table. Demir produces a varied and creative tasting menu and his signature dish, beef cheek tacos, are to die for. The space is tiny so booking in advance is essential.

Today Sülüklü Han is a popular spot to have a drink in the evening. The Sülüklü Han Collective has been producing wine made with grapes from the Elazığ province, for years and their wines go well with a slice of fresh white cheese. Taxes on wines in Turkey are extremely high, but the Collective aims to keep their prices as low as possible.

Taxi driver’s food suggestions we didn’t make it to

I confess I’m a big eater but there’s only so much you can consume in a day, so we didn’t make it to the following places. If you do I’d love to get your feedback.

Mardin Kebab Evi

Merkez Lahmacun in Bakircilar Çarşı (Cyrus and Safi don’t eat wheat so this is on my list for next time)

Omar Usta in Mardin Kapısı for Hindi Pilau (Turkey rice)

Food sold by street vendors

There are mobile tea carts, çiger mangal (liver grills) and stacks of thin simits called yağlı or yayla (I couldn’t catch the spelling so am happy to be corrected) all over the place so you’ll never go thirsty or hungry.

Diyarbakir muz, ‘Diyarbakir bananas’ look nothing like their name, with thin green stalks covered with a reddish bubby texture of something, I don’t know what. I learned the name from three Istanbullu guys I saw buying some. One of them gave me a piece to try and all I can say it has an odd taste. I can’t be more specific than that.

More appetising to both the eye and the palate were barrows piled high with sweet young ışık, sugarcane, and wheelbarrows full of yeşil nohut (green or young chickpeas). Yeşil nohut is sold in large bunches thick with clusters of furry almond shaped pods.

What to bring back from Diyarbakir

Remember the antique jewellery shop I mentioned? Owned by Hüseyin Diril (mobile number 05512172635), it’s located on the first floor of the Hasan Paşa Hani. Hüseyin Bey sells a range of new and antique silver jewellery as well an eclectic selection of objet d’art. I came away with a beautiful pair of earrings made from ruby offcuts and an ongoing yen for another pair that were out of my price range. Sigh.

Down near Ameditan there are shops selling all sorts of cheeses and the most delectable incir reçeli, fig jam, ever. They’ll happily package it up for you and my jar survived the flight home, wrapped in my dirty washing.

Kurdish coffee is another popular souvenir. There are several types, including menengiç, coffee sometimes made out of pistachios but more usually out of the fruit of the terebinth tree, with its turpentine-like flavour, and dibek. Dibek gets its name from the Kurdish word for mortar, dibek, used to crush the coffee beans in a stone pestle. The resulting coffee grinds are fairly course with a rich texture, resulting in a softer and less bitter coffee taste.

Everywhere she travels, Safi buys a new strand of tespi, worry beads for her mother. There are dozens of men selling them at the entry to Ulu Camii, but she liked a particularly lovely and fairly pricey strand for sale from a man called Murat. Murat explained to us they were made from secang, wood from a tree native to tropical Asia. We were amazed that worry beads being sold in south east Turkey had come from so far away, and even more surprised when Murat showed us his Youtube channel.

How to get to Diyarbakir and other practical information

The quickest way to get to Diyarbakir from Istanbul is to fly. It’s important to know Istanbul has two airports, one on either side of the Bosphorus. Budget airlines like Pegasus and Ajet depart from Sabiha Gokcen Airport on the Asian side of the city, while Turkish Airlines leaves from Istanbul Airport. I generally use Expedia when I’m looking for plane tickets.

Depending on what country you’re from, you might need to get a tourist visa in advance. Here’s everything you need to know.

Another thing you should do in advance is book your accommodation because if you leave it to the last minute you might be disappointed with the options available. I’ve been using Booking.com for years now (hello Genius!).

These days travelling without WiFi coverage is inconceivable, and eSIM are the way to go. I recommend Truely, an eSIM provider working with local telcos meaning you don’t need to worry about workarounds like you do with other providers. I like that you can opt to buy 1 to as many days as you need, instead of being limited to 7, 15 or 30 days. Plus you can reload in country. Truely eSIM are straightforward to install and activate but if you have any problems their responsive Whatsapp customer service is available 24/7.

Use my code: insideoutinistanbul and get 5% off when you order through the Truely website.

Lastly, if you’re travelling alone, check out my post on useful solo travel tips Turkey for women (and men).

However you travel, welcome to Turkey, have fun and stay safe.

Iyi yolculuklar!

Lisa i was lucky to visit Diyarbakir and Mardin several times between 2018 and 2022 as a close friend was in army there. I was taken to Mardin and some of the places you mention. I wish I had read your itinerary and descriptions before as I did not always know the history of the places I was viewing. I did not go when first invited as I thought it was dangerous but in fact when I did go felt no danger and wished I had gone sooner. The area that had been flattened due to fighting had not been made into the park when I was last there in 2022. I thoroughly recommend before visiting places reading your books. Diyarbskir old town is amazing and shops built into caves in the wall were selling souvenirs of the colourful materials used to cover small tables and stools in the çay houses. I was surprised also by the modern shopping malls close to the old area

Yes, Diyarbakir is a wonderful place with so much history, great food and warm welcoming people, despite the troubles they’ve seen. Even though you didn’t know all the history I’m sure you would have seen and done things I didn’t because when you go somewhere with Turkish friends it’s such a different experience.