Liberation of Istanbul

When I studied history at high school we learned about World War I from an Antipodean perspective. Heroic Australian Johnnies fought local Mehmets at Gallipoli, the Germans were eventually defeated and everyone went back home again. What we weren’t told was what happened next in Istanbul and Turkey.

Even before the war came to an end villagers of various ethnicities faced assaults by Muslim çete (brigands) and battalions from mainland Greece. Then, when the rest of the world picked itself up and resumed civilian life, from 1918 to 1923, Turkey was occupied by the Allies. For almost five years British, French and Italian troops were based all over the country, in cities like Izmir, Gaziantep and further afield. They were also stationed in Istanbul during what Turkish historians refer to as the Mütareke period, the truce*, and it was divided into three phases. The first phase started with the signing of the Armistice of Mudros on October 30, 1918 and ran until March 16, 1920. When signing the agreement, the British representative Admiral Gough-Calthorpe explicitly told Ottoman signatory Rauf Bey that Istanbul would not be occupied but the powers that were in London had other ideas. As early as mid-November 1918 Allied warships began to drop anchor in Istanbul.

During this five year period roughly half the city’s inhabitants were Muslim, with around 400,000 Rum, Greeks born in Turkey, 120,000 Armenians and 45,000 Yahudi, or Jews. The balance was made up of Levantines, Poles, Italians, the English and an assortment of other foreign born peoples. When thousands of displaced people started flooding into the city the population was pushed up to around the 1.2 million mark. They came from other parts of the failing Ottoman Empire in search of refuge, or were fleeing the allied colonies, war torn states, the Balkans and parts of Russia. In November 1917 alone, upwards of 200,000 Russians had arrived in Istanbul, fleeing the Bolshevik October Revolution. In November 1920 more came, sailing from Sevastopol to Istanbul because it was the shortest and safest way to get out of Russia. Members of the Vrangel Army, soldiers exiled after the Czarist armies were defeated, arrived along with Russian aristocrats, the so called White Russians fleeing capture by the Red Army.

Just as they had decided in the heat of battle who would have control of which part of the Ottoman Empire post war, the Allies divvied up Istanbul. The French were given Topkapı Burnu, that is Sultanahmet, the British took charge of Beyoğlu and the Italians got Üsküdar. At the insistence of the British, people suspected of war crimes were arrested and sentenced to death, sometimes by the courts but also through secret plots and assassinations, planned and carried out in high class hotels and shabby bars. One case involved the district governor Kemal Bey of Boğazlıyan, Yozgat Province. Indicted for ordering the deportation and extermination of 40,000 Armenians, Kemal Bey was found guilty and hanged on April 10, 1919. His death sparked huge demonstrations against the powers of the Allies. When Greeks troops and irregulars occupied Izmir in the following month**, people held protests in Sultanahmet, Fatih, Üsküdar and Kadıköy. In early 1920, more than 10,000 people came together to express their resistance to the Allies presence in Istanbul.

As a response to such huge scale loss, grief and need, many Istanbul residents and hastily formed associations set about improving their lives and those of others. Charities held fund raisers to support newcomers to the city, orphans, injured soldiers and the poor. New schools were opened, cultural events were arranged and the press expanded exponentially, fed by a swirl of ideas and possibilities. A raft of newspapers appeared on the streets produced by Turkish nationalists, socialists and communists alongside minority publications written in Greek, Ladino and Armenian with broadsheets in English and French catering to the invaders. Intellectuals debated how to tackle the occupation of the city and soldiers argued for armed resistance. In the universities a line was drawn between professors who supported the Milli Mücadele, the national struggle and those who did not. Students went out on strike in response.

There was no one religious group, language base, cultural norm, monoculture or uniform set of actions behind the fervour besieging the city. There was no need. All everyone wanted to know was, once the dust settled, who would Turkey belong to and what would it look like.

With their future uncertain and stricken by the loss of sons, brothers, uncles and husbands, Istanbul and its original residents were in turmoil. Yet despite the hardships people were suffering, change seemed imminent. Soldiers and those loyal to their country were working behind the scenes to ensure Turkish sovereignty. Of course, one name stands out, that of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, who went on to become the country’s first president. While Ataturk was a key figure, he didn’t fight singlehandedly. The country’s success in the Turkish War of Independence was as much a result of the brave actions of ordinary men and extraordinary women like the 83 martyrs in Gaziantep and individuals like Nakiye Elgun and Şerife Bacı, who all committed themselves to freedom.

The protests that had started during the first phase of the truce grew in number and strength during the second. Although May Day processions were largely made up of union movements and members of various left-wing political parties such as the Socialist Party of Turkish Workers and Farmers, they were clearly directed against the occupiers. Unemployment was rife in Istanbul and there was a severe shortage of skilled workers, meaning wages were low. There were jobs to be had, especially in the lignite mines in Thrace that supplied the Silahtarağa Electricity Station in Istanbul but instead of training up locals, the British brought in workers from China.

Battles had been ongoing between Greek and the depleted Turkish troops throughout the country since 1919, and slowly but surely the Turkish soldiers began to claw back control. The decisive clash took place over six days in Dumlupınar, ending on 30 August 1922. It’s now commemorated every year as Zafer Bayramı, Victory Day.

The second phase of the Mütarek came to an end when the Sultanate was abolished on November 1, 1922. The Allies continued to control Istanbul until the Turkish War of Independence officially ended on July 24 (coincidentally my birthday) in 1923 with the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne that recognised the Grand National Assembly in Ankara as the legitimate Turkish government. This signalled the official end the Mütareke period although Allied troops remained in Istanbul until October of that year. They finally departed on October 4 and then on October 6, 1923, the first official soldiers of the new Turkish government, led by Paşa Şükrü Naili entered the city.

*********************

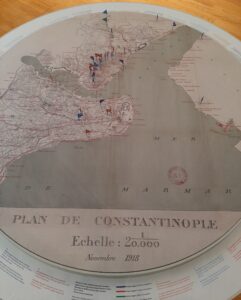

*You can learn more about this important period of Istanbul’s history at the “Occupied City: Politics and Daily Life in Istanbul, 1918–1923” exhibition. It’s on at the Istanbul Research Institute and runs until 26 December 2023.

**The Greek-Turkish War requires its own post by an historian, which I’m not, but I recommend you have a look at this paper by Nazan Maksudyan. It’s based on the 20 articles written by American writer Ernest Hemingway when he came to Istanbul in late 1922 on assignment for the Toronto Star.

************************

Planning to come to Istanbul or Turkey? Here are my helpful tips for planning your trip.

For FLIGHTS I like to use Kiwi.com.

Don’t pay extra for an E-VISA. Here’s my post on everything to know before you take off.

However E-SIM are the way to go to stay connected with a local phone number and mobile data on the go. Airalo is easy to use and affordable.

Even if I never claim on it, I always take out TRAVEL INSURANCE. I recommend Visitors Coverage.

I’m a big advocate of public transport, but know it’s not suitable for everyone all the time. When I need to be picked up from or get to Istanbul Airport or Sabiha Gokcen Airport, I use one of these GetYourGuide website AIRPORT TRANSFERS.

ACCOMMODATION: When I want to find a place to stay I use Booking.com.

CITY TOURS & DAY TRIPS: Let me guide you around Kadikoy with my audio walking tour Stepping back through Chalcedon or venture further afield with my bespoke guidebook Istanbul 50 Unsung Places. I know you’ll love visiting the lesser-known sites I’ve included. It’s based on using public transport as much as possible so you won’t be adding too much to your carbon footprint. Then read about what you’ve seen and experienced in my three essay collections and memoir about moving to Istanbul permanently.

Browse the GetYourGuide website or Viator to find even more ways to experience Istanbul and Turkey with food tours, visits to the old city, evening Bosphorus cruises and more!

However you travel, stay safe and have fun! Iyi yolculuklar.

“ Turkish War of Independence officially ended on July 24 (coincidentally my birthday)”

I’ve booked a trip to Türkiye for my birthday, which, coincidentally, is October 29. Nice to know our birthdays are significant dates in Turkish history!

That is quite a coincidence! Are you flying Turkish airlines when you come? I imagine they’ll pull out all the stops on the day.